Frank Frazetta artwork stretches far beyond comic books, paperbacks, and posters. If you’ve ever spotted fantasy scenes airbrushed on panel vans or shouted, “By the power of Grayskull,” you’ve got the Grandfather of Fantasy Art to thank.

Frazetta’s paintings and sketches are famous for their celebration of movement and the human form. But where did the Brooklyn native draw the inspiration for his iconic style?

Frank Frazetta's artistic origin story

"I want to do something that nobody has done before me. And I want to do it in such a way that nobody will forget me for it."

As a kid, Frazetta pored over comic strips and cartoons like Tarzan, Prince Valiant , Li’l Abner, and Popeye. Aside from the occasional petty crime and amateur baseball games, his entire life seemed to have revolved around comic books.

By 16, Frazetta was removing pencil lines and ruling panel borders for DC Comics legend Bernard Baily. He eventually apprenticed under Ralph Mayo and horror illustrator Graham Ingels (who would later become his editor), creating art for comic books and daily strips.

Maintaining creative control & authenticity

Frazetta spent his 20s and early 3os moving through superheroes, science fiction, and westerns. But the turning point of his career–and one of the happiest periods of of his life–was working for legendary horror publications Creepy and Eerie

While the pay was low, editor James Warren gave him free rein to create whatever he wanted. This freedom had a profound influence throughout his life.

Fun fact: Though Disney’s illustrious animation department offered Frazetta a job, he turned it down to remain in New York City.

Typically, Frazetta would receive simple prompts from clients and let his mind run wild. Unlike many of his peers, he maintained creative control–even with commissioned work. There was no compromising Frank Frazetta’s style.

"I didn't paint any of that barbarian stuff because I wanted to. They were paying me!"

"That barbarian stuff"

Frazetta’s maverick streak is epitomized by the Conan the Barbarian series.

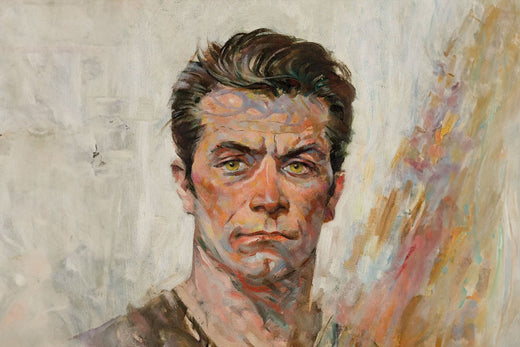

In 1966, Frazetta was assigned to generate cover artwork for Robert E. Howard’s collection of stories. Howard (founder of the sword and sorcery genre) had written them back in the 1930s, but they’d never been artistically rendered.

"I went right ahead and created this character that didn't even resemble Howard's description at all: Mine is quite a different guy. He was what I thought a barbarian should look like. The ultimate barbarian."

While it might have been a paid piece, Frazetta’s iron-clad style and vision meant that Conan became one of his most recognizable works of art.

Frank Frazetta's influences

When you stare at Conan (or any of his pieces, let’s be honest), Frank Frazetta art sits at the unique intersection of science fiction, classic Flemish masters, Pre-Code Hollywood, early comic books, and body worship. He defined a genre that’s impossible to put your finger on–but you know it when you see it.

Hal Foster

One of the most celebrated comic illustrators and storytellers, Hal Foster is most famous for his adaptation of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan and Prince Valiant cartoons. When speaking about the former, Frank Frazetta stated that it was, “perfection, a landmark in American twentieth-century art that will never be surpassed."

"Foster would be my main influence. From the sublime to the ridiculous... His ability to simplify and tell a story, that's a great artist."

Hal Foster’s heroes struggled against the exotic and unknown. Jungles teemed with hanging vines and wild cats. Unscalable cliffs and ancient citadels lurked with evils.

While “Nina” (1951) was never published, it is one of the finest examples of Frazetta’s comic work, and he admitted that these fantasy images were inspired by Foster. It’s certainly easy to see similarities. But while Foster created worlds within comic strips, Frazetta was able to do so in single canvases.

"A sexy girl lost in some strange land by herself... why not?"

Within a few decades, Frazetta’s work was less about “good versus evil” and more about the fight for survival. It’s more about the adventure itself, with muscular vikings traipsing wastelands, witches beckoning to heroes, and warriors slaying bloodthirsty beasts.

King Kong

Frazetta claimed to have watched King Kong more than 4,000 times, and that left a deep impression on his aesthetic:

"The total work of art. The hazy, misty, wonderful quality of it is something I always shoot for. That mystery, that sense of wonder. That's what I try to capture."

While some might consider it primitive by modern standards, King Kong accomplished what no other film had done: develop a stop-motion character with believable visual effects. Straddling the line of jungle adventure, horror, and thriller, it’s a cultural touchstone for cinema lovers. And it’s easy to see the parallels in Frank Frazetta paintings, with exotic animals, ethereal maidens, vine-choked trees, and raw, animalistic power contained in a corporal frame.

Peter Paul Rubens

"My paintings are like classic Rubens or Michelangelo, but unrestrained."

Flemish Baroque master, Rubens (1577-1640) is best known for painting the human form with incredible depth and movement. Men are given tanned, robust physiques that brim with kinetic energy. Sylph-faced, voluptuous women are shapely with mortal “flaws” like cellulite, folds, and dimples (as seen in as seen in “Venus and Adonis”).

Take Rubens’ models, pump them with steroids, and you’ll get Frank Frazetta women: pulp pin-ups with slim waists, visible ribs, and near-to-bursting hourglass proportions. Whether creating pin-ups or sci fi art, these forms had the perfect blend of power and softness. The artist never shied away from capturing subtle imperfections either.

Movement and light

Rubens was one of the first painters to master movement. This “Three Graces” prototype captures a gentle dance (evident by the positioning of feet and gauzy material). Using few colors, the bold contrast between light and dark is maximized with a highlight across the models’ skin.

Frazetta’s fantasy drawings and paintings are famous for their kinetic energy and hazy-dream-like linework. In this Frank Frazetta print, the foreground erupts with colorful foliage while the figure receives a light-handed, ethereal treatment that’s attributed to Rubens. Even though the subject is at rest here, her hair blows gently in the wind.

"Really, there's so little color that I might use it very sparingly as a focal point... muted coloring, soft-tinted areas, and suddenly, a bright spot!"

Michaelangelo's anatomy lessons

In the world of art, Michaelangelo was best known for anatomical drawings, viewing the human form as a piece of architecture created by God. His human proportions didn’t just imitate Nature: They perfected it.

Both artists captured the human form with detail and dynamism, as though their subjects were about to burst out of their skin.

"I've always just understood perspective and space. I just had an eye for it. Some people are born with it, some aren't. I simply didn't focus on anatomy... I was faking my way through it."

Frazetta may not have dissected corpses for inspiration, but he drew from a well of men’s magazines, pulp publications, and his own imagination to take his characters to the next level.

Butts, rears, and posteriors

We can wax philosophical on the depth and layers of Frank Frazetta art all we want. But we can’t can’t overlook his profound fascination with buttocks. In the artist’s own words:

"I am definitely an ass man."

While many artists tend to fixate only on female beauty, Frazetta was an equal opportunist: His collective work contains an endless array of perfectly formed backsides of all genders of creatures.

"It blows my mind. Talk about simple shapes. Two very simplistic curves. It's so dumb, but they are fascinating as hell. It's more than that. It's the way the rest of the anatomy ties into that area -- incredible beauty."

While many artists tend to fixate only on female beauty, Frazetta was an equal opportunist: His collective work contains an endless array of perfectly formed backsides of all genders of creatures.

Frank Frazetta artwork: where gold meets the canvas

Frank Frazetta art is exceptional in every sense, and that ethos drives MetalMark to create our singular gold art pieces. We’ve worked directly with his family estate to introduce something truly extraordinary: officially licensed Frazetta prints on the world’s first golden canvas.